From Chaos to Clarity: Tackling Information Overload in the Digital Age

8 min read

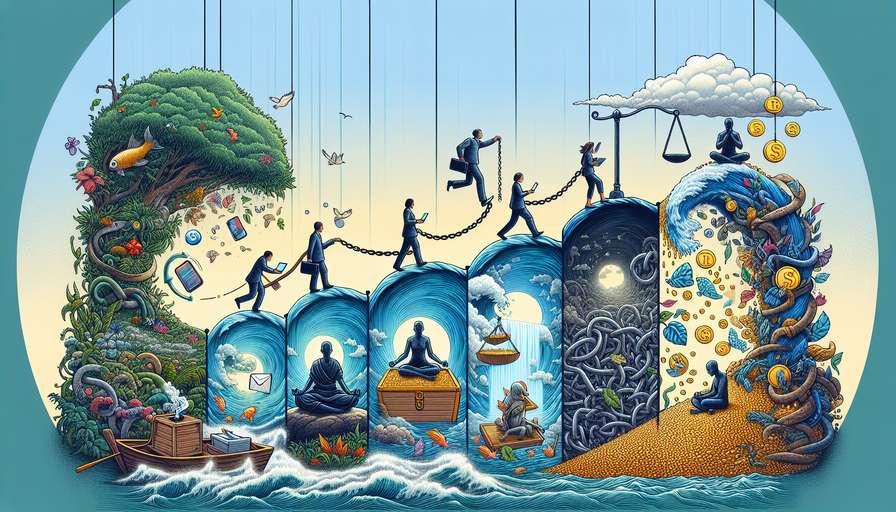

The text talks about the problem of information overload, which means having too much information to handle. In today's world, we get a lot of information through emails, social media, and the internet, making it hard to keep up. This can hurt our well-being and make it difficult to make good decisions at work. For example, when someone gets interrupted by an email, it can take them almost 25 minutes to focus back on their work.

With Long Summary technology, this article distills the long original content into a concise format.

The author mentions that this issue isn't new; it started with the invention of the printing press, which made it easy to create and share lots of printed materials. Now, with technology, anyone can publish information online without much effort. We receive information in many ways, like text messages, Facebook alerts, and emails, which can feel overwhelming.

However, there is hope. New tools and techniques can help manage this flood of information. Some tools can sort and prioritize emails, while others encourage people to change how they think about information. The author hopes that one day they will enjoy the vast amount of information instead of feeling overwhelmed by it.

Today, we have a lot of information coming at us from different places like wikis, social media, and work emails. This can be stressful because people feel they need to respond quickly to everything. Experts like psychiatrist Edward Hallowell say this can lead to something called "attention deficit trait," which makes it hard to focus. Linda Stone, who studies how we pay attention, even found a strange issue called "e-mail apnea," where people forget to breathe normally while checking emails.

A study showed that distractions from emails and calls can lower people's IQ by 10 points, which is more than the drop seen in people who smoke marijuana. While some people enjoy this constant flow of information, others can become addicted to it. A survey found that many people check emails in places like the bathroom or even during church, showing how it mixes work and home life.

Companies also suffer because employees waste time sorting through unnecessary emails. A survey showed that workers spend about two hours a day on emails, with many considering one in three emails useless. Overall, information overload costs the U.S. economy $900 billion each year.

People often suffer from constant interruptions, but they don’t fight back because they think communication is good for them. Zeldes, the president of the Information Overload Research Group, explains that when we get distracted by emails or notifications, it takes a long time to get back to our original task. A study showed that after being interrupted by an email, it took people about 24 minutes to refocus on what they were doing. During this time, they often checked other emails or did unrelated things like texting friends or browsing the internet.

More than half of the time spent off task happens after people feel ready to work again. They get distracted while trying to remember what they were doing or switching between different applications. Research also shows that interruptions can reduce creativity and that even young workers need uninterrupted time to complete challenging tasks. Additionally, waiting for email replies can slow down decision-making because people wonder if their messages were ignored or lost in a crowded inbox. This uncertainty can be more frustrating than just waiting for a response.

Our minds often get overwhelmed when we wait for replies to emails. We think about how long it usually takes someone to respond and whether we should follow up or try to contact them in different ways. This waiting can hold up our work, even though the answer might only take a minute. A study found that Intel loses almost $1 billion each year because of wasted time from too many emails and interruptions.

To manage this information overload, some people use technology wisely. For example, Jerry Michalski, a consultant, uses social media to ask for information and gets quick responses. He also uses a tool called TheBrain to organize and save useful information. Michalski believes it’s important to let go of the need to know everything. He relies on social networks and tools like Twine to filter and find information that matters to him. This way, he doesn’t feel overwhelmed and can focus on what’s important. Many people struggle with email stress, but using the right tools can help manage it better.

The text discusses how to manage the overwhelming amount of information, especially emails, that people receive. It suggests using new software tools that can help organize your inbox by prioritizing important messages, sorting emails by projects, and filtering out irrelevant ones. Some tools can turn emails into tasks or appointments and even track how much time you spend on emails.

For those who feel addicted to checking emails, a Google engineer created a feature for Gmail that reminds users to take breaks, encouraging them to step away for 15 minutes. The text emphasizes that overcoming email addiction requires personal effort and changing your habits. It suggests following productivity methods, like David Allen’s “getting things done” approach or setting limits on how often you check your inbox.

Additionally, it encourages letting go of guilt about not responding quickly and accepting that you can’t read every email. Some people even consider “email bankruptcy,” which means deleting all messages for a fresh start. Overall, the text highlights the importance of finding ways to manage information better for both individuals and companies.

Managing email can be really hard, especially with so many messages coming in. Christoff, who works at Morgan Stanley, is trying to help employees deal with this problem. He and his team created special software that helps sort emails by importance. It can tell which messages are urgent and which can wait, based on who sent them and the user’s past behavior. However, if people don’t trust this system, they might still check all their emails, which can be distracting.

Many companies are starting to realize that helping employees manage email better can be good for everyone. Some new tools are being tested to control how many emails people send. For example, a tool called Postware makes employees use a “stamp” for each email, limiting how many they can send each day. Another tool, Attent, gives users virtual currency to show how important their emails are, helping others decide which messages to read first.

There are also new ideas being developed that can sense when someone is busy and delay email alerts, making it easier for people to focus on their work.

IBM is developing a program called IM Savvy, which acts like an answering machine for instant messages. It can tell when you are busy by noticing your typing or mouse movements. If someone tries to message you, IM Savvy will let them know you are unavailable but allows them to interrupt if it's really important. Jennifer Lai, who leads the IM Savvy team, warns that if the software makes a mistake and doesn’t interrupt you when needed, it could cause problems.

To help with the overload of emails, companies need to change how people behave, not just use new technology. Nathan Zeldes created a tool called the Intel Email Effectiveness Coach, which helps people avoid email mistakes before sending messages. For example, it can warn you if you are about to hit “Reply to All.”

Companies can also set rules for how to communicate better. They might have a “no email morning” to give everyone time to work without interruptions. Managers can encourage using phone calls instead of emails when discussions get too long. Overall, companies should think about better ways to share information to reduce email overload.

The IT department can help with email problems by creating automatic replies that let senders know when they can expect a response. This way, if someone needs an answer quickly, they can call instead of waiting for an email reply. This can help avoid misunderstandings about how fast emails should be answered. For example, if one person thinks emails should be answered right away and another thinks they can wait, it can lead to frustration.

Sometimes, strict rules are needed to manage email overload. For instance, a company leader once stopped the "Reply to All" feature in emails because it was causing too much confusion. It's important to remember that what seems urgent to one person might not be important to someone else, and interrupting them can be costly.

To deal with too much information, organizations need to find a balance between what senders want and what recipients can handle. Researchers also struggle to keep up with the growing number of scientific papers, which increases by about 8-9% each year, making it hard to stay informed.

Researchers today have a lot of work to do, like experiments, writing grants, and publishing papers. With so much new information coming out, keeping up with it can feel like a second job. To manage this, some researchers team up. For example, Lawton Chung and his classmates from Stony Brook University started a 'journal scan' where each person checks different scientific journals and shares interesting papers with the group every month.

Others use online tools to stay updated. Pavlo Kochkin, who studies atmospheric physics, uses a site called Feedly to organize his reading list. He checks about 100 paper titles each day and has alerts set up to catch important publications. Chemist Peter Robinson reads scientific papers and also keeps up with technology and business news, spending 1-2 hours reading daily.

Networking is also important. Adam Thomas from the National Institute of Mental Health uses social media and lab meetings to learn about new research. He believes we need people who can help sort through all the information and explain why certain studies matter. Blogs like Dynamic Ecology help researchers stay connected and informed.

Researchers often share ideas and ask questions in online communities, which helps everyone understand information better. However, meeting in person at conferences and seminars is also very important. These gatherings allow scientists to catch up and discuss new findings. Chung, who will start a new job at the University of California, Irvine, believes that talking face-to-face helps build a sense of community and teaches newcomers about the field.

Some scientists, like Elisabeth Bik from Stanford University, create their own systems to keep up with research. She started by setting up alerts for new papers about microbiomes. As the field grew, she began sharing her findings with her coworkers and eventually created a blog called Bik's Picks, which gets hundreds of views daily. She spends a lot of time each day reading and selecting papers to share, but her boss allows her to use work hours for this because it helps everyone in the lab.

In other fields, sharing research before it is officially published has been common for years. For example, arXiv.org has been a place for scientists to share their work since 1991.

In 2009, a person named Guillochon started a website called Vox Charta. This site is like arXiv, but it focuses on discussions about astronomy and astrophysics papers. On Vox Charta, scientists can vote on which papers they find most interesting. This helps them decide if they want to join discussions about those papers. Because the site is mostly automated, Guillochon doesn’t have to spend much time managing it, just keeping it running smoothly.

Last September, two physicists created a new site called Benty Fields, which covers all types of arXiv papers. Benty Fields allows researchers to make reading lists and vote on which papers should be discussed next. It works like a social network where users can create profiles, upload their resumes, and follow each other.

In today’s world, it’s hard for scientists to keep up with everything by just reading a few journals. They need to find good sources of information for their work. Jacob believes that thinking about how we get new information can help scientists become better at their jobs.

Notice: The above is an AI-generated summary by the Long Summary tool and does not substitute for the original source material. Users are responsible for confirming the accuracy of the summary and adhering to applicable copyright laws.

We use cookies to enhance your experience. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more